This day the weekly bills come out

To put the people out of doubt

How many of the plauge do die;

We sume them up most carefully—– Henry Climsell. “London’s Vacation, and the Countries Terme”1

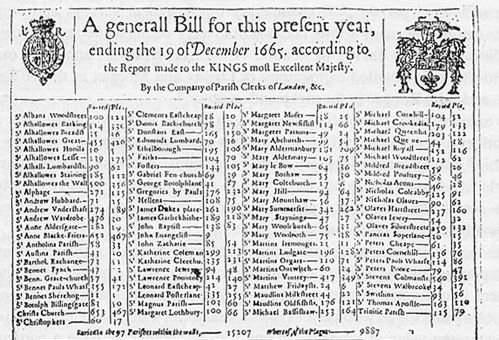

Bill of Morality, 1665.

Although morbid, it’s fascinating to read a recent article in the NYT about efforts in Sierra Leone to use “electronic autopsies” in a large scale attempt at counting deaths.

According to the article, this undertaking is part of a broader effort at data collection, including questions on age, religion, marital status, etc. The novelty, it seems, is in trying to be thorough with respect to what people have died of (including extensive questions about symptoms), even though this information is being collected potentially long after the fact. Although those asking the questions do not have the requisite expertise, physicians will eventually review the data collected from the survey and assign a formal cause of death to each.2

The complexities and political dimensions of determining cause of death are now much more familiar to all of us these days, given the issues that have emerged around what gets counted as a death from Covid-19. Beyond such recent developments, however, counting the dead is interesting in part because it was instrumental in the early development of epidemiology and biostatistics. Most famously, John Graunt in 1662 was among the first to analyze such data systematically, in his case based on the English “Bills of Mortality”.

According to various accounts, church parishes in England began recording major life events in the 1560s, including births, deaths, and Christenings. By the early 1600s, publication of these records became fairly common and systematic, especially when waves of diseases were passing through the country, such as plague and smallpox.3 The “searchers” who compiled these records for aggregation by a central authority endeavoured to state “of what disease every particular partie in their Bill menconed dyed soe neere as they can learne or understand.”4

Although these records were highly biased (including only Anglican parishioners, for example), and likely rife with errors (especially regarding cause of death), they were still adequate for Graunt’s early efforts at trying to estimate various population statistics, including birth rates in various parts of the country, distributions of death by gender, and whether epidemics correlated with certain events, like the ascension of a new monarch.

In particular, Graunt is credited with a number of notable discoveries, including that urban death rates were higher than rural, but that the urban populations were stable or growing thanks to migration from the countryside. He also found the mortality rate of children to be dire, with roughly one third of children dying before the age of five, and that deaths from “chronic or endemic diseases” were actually more common than the epidemics that people were most afraid of.5

In many ways, Graunt was ahead of his time, and this sort of analysis seems to have had relatively little impact until centuries later. By the early nineteenth century, however, the systematic collection of population statistics about disease, education, and crime had become prolific in Europe, along with the emergence of a biopolitical infrastructure that has been extensively discussed by the likes of Ian Hacking and Michel Foucault. Hacking in particular notes how the counting of information about people leads almost inevitably to the creation of categories (such as causes of death) that come to define, in part, our social reality. As Hacking writes, “it is illegal to die, nowadays, of any cause except those prescribed in a long list drawn up by the World Health Organization.”6

It is not hard to imagine the kinds of benefits that might result from having this information available, especially for a competent and well-intentioned government. In the case of Sierra Leone, the data apparently revealed, for example, that older adults were dying from malaria at much higher rates than had been previously thought, in part due to a common misperception that surviving malaria in childhood would provide lifetime protection.

On the other hand, it is important to remember that such information also feeds directly into the ability of the government to manage and control populations. The original purpose of the Bills of Mortality, after all, was to help city aldermen decide where to impose quarantines, and which houses to board up.7 Graunt’s patron, Sir William Petty (also an amateur demographer), seems to have jumped rather quickly from studying population patterns, to proposing interventions such as “annual fines for women over eighteen who bore no children in any given year.”8

In addition, we are often all too ready to assume that more information will necessarily lead to better policies, or that observed improvements were the result of well-made decisions. The article on Sierra Leone suggests, for example, that lower-than-expected maternal mortality “showed that resources being poured into making childbirth safer for women and babies was paying off”, but this may or may not be a justified inference. Similarly, in the U.S., there is vastly different tolerance for deaths from different causes, often without good reason. Extremely strict regulation ensures that flying results in essentially zero fatalities, which we might contrast with the way the country approaches automobiles, guns, and prescription drugs.

Although we could certainly benefit from more sensible policies on some of these issues, we should resist the temptation to assume that lack of data is the only obstacle to change. According to the NYT article, “the W.H.O. is encouraging countries to treat vital statistics data as they do other forms of infrastructure, such as gas systems or electrical grids.”

Again, data and models can clearly be useful. The U.S. government’s highly effective pre-commitment to buying Covid-19 vaccines was clearly based on models of how serious that virus would be for the country. Unfortunately it can be dangerous to assume either competence or benevolence on behalf of those collecting the data. There has already been at least one Covid-19 testing service, for example, whose policy allowed the company to sell participants’ genetic data to third parties.

In sum, with ever-expanding corporate and governmental data collection, biopolitics and governmentality remain more relevant than ever. As important as Hacking’s insights about the emergence of categories are, the sheer volume of raw data being collected perhaps means that we need to begin thinking more about not just categorization, but even farther back, to the original impulse to record and archive in any number of forms, and the trajectories of such records.

Quoted in James H. Cassedy. Demography in Early America. Harvard University Press, 1969. ↩︎

The numbers here are interesting: a previous survey interviewed 343,000 people in 2018 and 2019, which led to information on 8,374 who had died. Although that is enough to get a very good estimate of common causes of death overall, it seems sure to miss much of the long tail, especially once things get broken down by subcategories. ↩︎

J. C. Robertson. “Reckoning with London: interpreting the Bills of Mortality before John Graunt”. Urban History 23(3), 1996. ↩︎

Quoted in J. C. Robertson. “Reckoning with London: interpreting the Bills of Mortality before John Graunt”. Urban History 23(3), 1996, footnote 25. ↩︎

Daniel R. Headrick. When Information Came of Age. Oxford University Press, 2000. ↩︎

Ian Hacking. Biopower and the Avalanche of Printed Numbers. In Biopower: Foucault and Beyond, edited by Vernon W. Cisney and Nicolae Morar. University of Chicago Press, 2015. ↩︎

Kristin Heitman. Of Counts and Causes: The Emergence of the London Bills of Mortality. In Research and Exploration at the Folger, March 13, 2018. ↩︎

James H. Cassedy. Demography in Early America. Harvard University Press, 1969. ↩︎